Delagrange uses a feminist approach to her proposal to include the visual in the rhetoric classroom because she views the situation in binaries where one side usurps the other:

- Male female

- Mind body

- Text image (94)

- Organizational inventional

- Abstract material (107)

- Logos pathos (155).

Her claim is that the male-dominated mindset of current rhetoric classrooms focuses on the mental over the physical and therefore accepts the use of text but rejects the use of images for conveying meaning. She wants us “to move beyond the historical privileging of the Word” (2); she encourages us to “reject discourses of immateriality that ask us to erase our embodied selves from our work, and we should take on all the roles necessary to develop convincing, principled, pedagogical performances in digitally mediated environments” (104). According to her, the concept of turning in a paper that is devoid of images and follows the required “white paper, 12-point black type, regular spacing, and otherwise defined formatting of the academic essay” (102) is repulsive. She wants “to subvert the widely-held mistrust of the visual in academic discourse by insisting that the material world cannot be reduced to language, that visual representations, including the visual components of words on a page or bars in a graph, contain meaning beyond mere text” (105). The fact that images do convey a different layer of meaning is well-explained and justly noted, but she seems to tip the scales too far to one side. If we are to teach students to evaluate what they are seeing and to explain what those layers of meaning are, we must teach them to verbalize what they see; visual literacy must include both the visual and words.

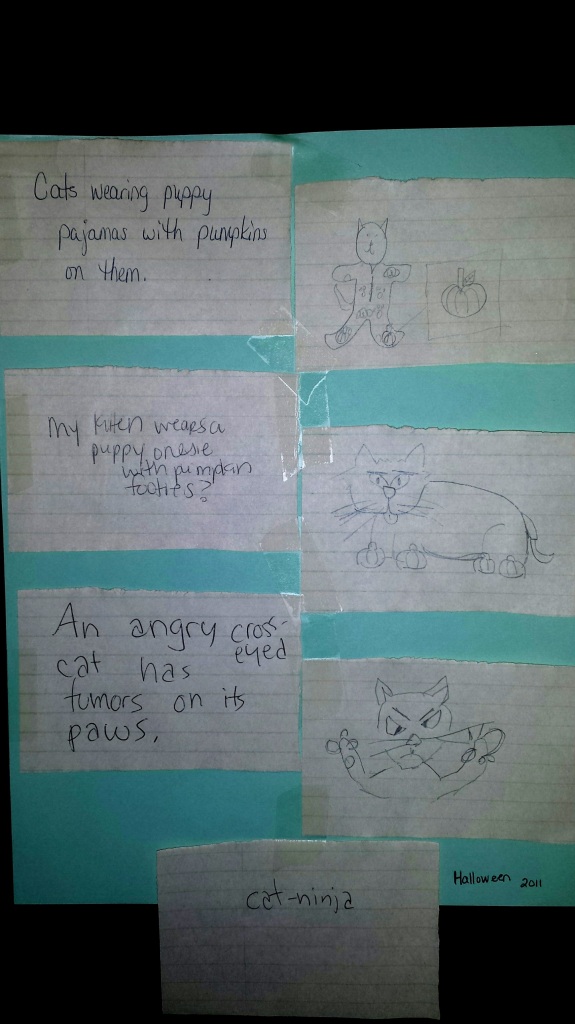

Let me explain the importance of both sides using an example from a party game from a few years ago. The concept of this game is similar to the game called “Telephone” where a message is whispered into the ear of one person who then repeats it to the next person around the circle; when the final person says the message aloud, it has usually deviated drastically from the original message. For this particular game, a group of ten people sat in a circle; we were all given ten squares of paper. The leader instructed us to write a description of any object on the first square of paper. We were to provide detail but not go overboard. We then passed our stack of papers to the left, so we were holding the description in our hands that someone else had written. We had to take the written description from the first square of paper and draw it onto the second square of paper. When we finished drawing that image, we passed to the left again. This time, we had to look at the image before us and try to describe on the third square the image we were looking at from the second square (we were not allowed to reference the original description). Once our descriptions were completed, we passed again and the process repeated itself. The interpretations between the written and the visual were usually humorous, but they showcased the need for discussion regarding both levels of meaning.

Delagrange devotes a few pages of text directly to refuting Robin Williams’s book The Non-Designer’s Design Book (2008), but her initial response defies Williams’ purpose. Delagrange complains that the four focal points of the book “oversimplify the design process, reducing it to a set of do’s and don’ts that entirely disregard rhetorical concerns of audience, purpose, and context” (102). She also complains that Williams encourages the production of advertisements which embody a “lack of ambiguity, and a (false) sense of unity and completeness and containment” (103), yet this is exactly what Williams is striving for. The illustrations which Williams uses are focused mostly on advertising, whether the example is a business card, a menu, or a flier trying to get an audience to come to an event or purchase a product. Williams wants to remove ambiguity so that the audience is inclined to respond to the advertisement. Since Delagrange is writing this book to an audience whose purpose is to explore rhetoric in the classroom, she is misguided in using Williams’ book as an example; they are simply trying to reach different audiences.

Delagrange also argues that “the rhetorical canon or arrangement should be . . . constructed today as a material, embodied techne’ which, through hypermediated linking of visual and verbal evidence, enables a process of wonder and discovery that promotes thoughtful inquiry and insight” (107). In my world, this is part of the pre-writing process for our students, but we expect them to take this “discovery” and “insight” and turn it into an essay.

- Delagrange, Susan H. Technologies of Wonder: Rhetorical Practice in a Digital World. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital P, 2011. org/wonder/ Web. 12 Oct. 2014.

This week I responded to Dan’s interpretation of the second half of Robin William’s The Non-Designer’s Design Book. He has an affinity for fonts that is fascinating, yet practical. Form does add an additional layer of meaning to content, and I like the fact that he focused on that concept using fonts specifically. Dan is just one of those people who is able to say a lot without saying a lot. Perhaps it’s just the male/female communication style difference that I am focusing on (as a female, I tend to ramble). Regardless of the “why,” I appreciate hearing from him and I consider his ideas worth paying attention to.

I also responded to Summer’s Part I of Lev Manovich’s Software Takes Command. Again, Summer has taken a tough concept, chewed it up, and spit it out in a manner that allows me to understand it. Summer is also very detailed, so that I can definitely use her information if I ever need to prepare for PhD comps! Manovich’s conversation regarding how much we rely on software is definitely warranted. Unfortunately, especially for the younger generation, we may be stifled by our over-dependence on these software programs. Then again, maybe I’m just being leery for no reason. Software is just another set of tools that we use, and we’ve been using tools as humans since we came into being. I do appreciate the ability to Google something whenever I have a question! But the fact that I can use the word Google as a verb speaks to the very conversation Manovich is having. I think I’ll add his books to my resource list.