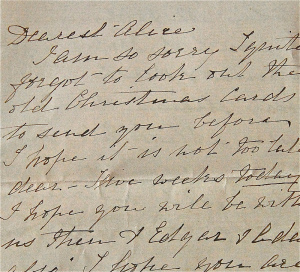

Once remediation as a concept is grasped, one can easily see that the idea is everywhere, not just in the digital media that we often think of when considering “New Media,” though its importance to the field cannot be overlooked. Citation references to Bolter and Grusin’s work indicate just how foundational the text is. Without stopping to notice remediation, both what we lose by no longer using the older medium and what we gain by using the newer medium, we make assumptions of our audiences and we risk failing to effectively communicate. For example, lacking a firm understanding of remediation, I may decide I want to exclusively communicate with family members via text or email, but both my grandmothers (ages 88 and 91) would prefer an “old-fashioned” hand-written note or phone call. One of them may be able to text, but it is a foreign language and a foreign concept to her. In addition to understanding the content of my messages, they would also hear the unspoken message, “I’m too busy to speak in a language that you naturally comprehend” which would send them a negative feeling to contradict whatever I’m trying to communicate.

3 Comments

I like that y’all include a link to the Google Scholar data on how often Bolter and Grusin’s work has been cited, but I am curious about how their ideas are used. Does anyone take their ideas a step further? Is there resistance to their conceptualization of remediation? Any ways for new media to break from remediation?

Ah, I see that I commented too quickly since y’all have a section engaging other scholars.

One thing that I am curious about specifically with your section on the importance of Bolter and Grusin’s work in the field is this idea that “we make assumptions of our audiences and we risk failing to effectively communicate” by not taking remediation into account. Since video games are what I know best, I’ll ask my question around that. For a medium like video games, people tend to emphasize the idea of “video,” likening the games to videos simply because the system links up to a television the way a VHS used to. However, videos and video games are very, very different entertainment media and the similarities usually begin and end with the visual and auditory elements. What happens when we put too much emphasis on the remediation and not enough on exploring on how innovative/unique a medium is compared to what has been deemed its “predecessors”?

Summer, I’m not really sure how to answer your question, but I can respond with another question: Who is the audience in a video game? Isn’t the player both the “author” and the “audience” in play? Yes, an obvious “author/creator” of the video game exists and without that person/group of people the game would not exist, but the player makes choices and by default becomes a sort of de facto creator herself, right? If this is true, then the player only needs to communicate and please herself, whereas my example of remediation regarding communicating with my grandmothers in the proper medium involves me the author meeting the needs of my grandmothers the audience.

I can appreciate, however, your concern for simply appreciating the creativity of a video game, especially as games become more and more realistic. Before I read Bolter and Grusin’s book, I had never considered remediation! While I think I can grasp the concept pretty well, I don’t let it remove the joy of watching (and being immersed in) a movie. (Side note: I’m reminded of Mark Twain’s comments about how mechanical the Mississippi River looked after he became a steamboat pilot; he mourned the ability to see merely the beauty of the river and not the swirls that told him something bad was hiding under the water.) Hopefully gamers will find a way to continue enjoying gaming and disregard the “what-is-vs-what-was” dichotomy.